Media playback is unsupported on your device

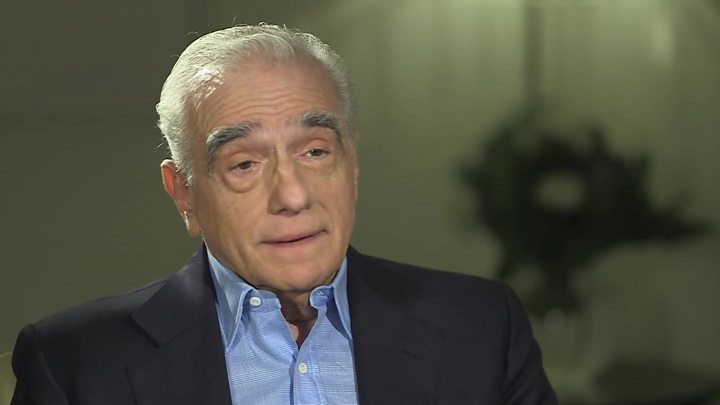

Martin Scorsese says he couldn’t get a Hollywood studio to back his three-and-a-half-hour mob movie The Irishman. “Nobody was interested in making a film with me and Bob [Robert De Niro] anymore,” he said. “I just think they thought the audience wasn’t there.”

Possibly.

Although I think they probably ran the numbers first. I mean, if you’re a studio exec and have one of the greatest movie directors of all time pitching an idea in a genre he’s made his own, starring Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Joe Pesci, you’d listen, wouldn’t you?

I imagine it came down to money and cautiousness.

Image copyright

Netflix

The Irishman sees the reunion of Joe Pesci (Russell Bufalino), Robert De Niro (Frank Sheeran) and Martin Scorsese for the first time in 24 years

The three male leads are all in their 70s, which is not a problem in itself, but the majority of their screen-time is spent when their characters are in their late 30s, early 40s. No amount of make-up was going to paper over those facial cracks. Stand-ins were discounted. Digital de-aging was the only option, but it had never been done in the way that Scorsese demanded: no green-screen, no image-capture head-gear – new technology was required.

Too risky, maybe. Would it work? Would it cost a fortune? Would the actors play ball?

Netflix stepped in and answered all three questions in the affirmative. But for all the very expensive high-tech trickery The Irishman is a staunchly old-school movie spanning half a century of mafia mischief in post-war America.

Classic Scorsese, you could say.

And so it is, up to a point. Cars are dramatically blown up, there are a lot of cold-blooded murders, and attention to every detail is paid with a historian’s soul and an artist’s eye.

Image copyright

Netflix

Martin Scorsese says The Irishman has “the rhythm of how we think when we look back on time”

The Irishman is a beautifully made film.

It is also very slow.

It starts with a long tracking shot inside an old people’s home, at the end of which we meet our elderly narrator Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), the eponymous Irishman. He tells us his story in a series of flashbacks in which we see a de-aged De Niro go from a trigger-happy American soldier to a trigger-happy Pennsylvania gangster working for mafia don Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci).

Scorsese says Pesci took a lot of persuading to put away his golf clubs and return to acting.

For Marty and for us it was time well invested. Pesci’s performance as the quietly-spoken, business-like organised crime boss is exceptional.

It will take something very special to deprive him of the Best Supporting Actor Oscar.

Image copyright

Netflix

Robert De Niro (Frank Sheeran), with Joe Pesci, who wasn’t keen to return to movie making, plays the role of the “quiet-don” Russell Bufalino

The spine of the movie is a road trip he takes with Frank (whom he calls “kid” throughout without even the smallest twinkle in his eye) to attend a family wedding. It’s a structural device that allows Scorsese to take all the side-tracks he needs to fill in the back story of the three inter-connected protagonists: Frank, Russell, and trade union president Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino).

Russell engineers a job interview for Frank as Hoffa’s wingman, which takes place over the phone. “I heard you paint houses”, Hoffa posits. “I do”, replies Frank, “and I do my own carpentry” – a line that wins an approving Sicilian smile form Russell.

They are not discussing DIY.

In a 1960s world of phone taps and wire traps, underworld America developed its own patois: hit men were known as house painters. Those who cleaned up afterwards did their own joinery.

It’s a central exchange in the film, establishing the crime triangle, the pecking-order of the protagonists, and the relationships that would develop.

Pacino is excellent, although slightly undermined by the de-aging process which, at times, makes him look more like the camp British TV host Larry Grayson than a tough-as-teak union leader.

Image copyright

Netflix

Oscar-winning Al Pacino had never worked with Scorsese before, and said “the character of Jimmy Hoffa was irresistible”

De Niro is also let down by the technology, which is a shame, because he is on top form. The facial changes are fine, they work. But it still leaves him with a body of a septuagenarian, which looks incongruous when moving stiff-hipped over rocks, or assaulting a local shopkeeper with arms pinned to his body.

It’s not a disaster, but it looks odd: it jars and distracts from an otherwise first-class film, which wears its duration lightly. In fact, the slow pace acts as another character, giving a very specific personality to the film, which is a re-telling of a true story made public in book form by Charles Brandt, a lawyer and friend of Frank Sheeran.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Pesci, Pacino, Scorsese, De Niro, and Harvey Keitel attending the world premiere of “The Irishman” in New York

Martin Scorsese says it is about “power, love, betrayal, and then, ultimately, the price you pay for the life you lead”. I said I thought it was also about old age, which elicited the sort of look you don’t quickly forget from the legendary helmsman.

“Old age?” he said, eyebrows raised.

“Yeah”, I replied, “it’s about the aging process”.

“The aging process”, he says and slowly and nods, “yes, the aging process ultimately… [pauses, smiles] without scaring an audience saying we won’t go and see a film about old age.”

A nerve unintentionally touched.

Perhaps the perception that it was a film about old folk was an issue when it came to financing.

Who knows. But it is.

That is the perspective from which the story is being told and rationalised: Sheeran is an old man facing his day of reckoning, like King Lear on the heath: not with two cruel daughters on his mind, though, but the two powerful masters he served.

It is a story of divided loyalties we’ve heard before, from 18th Century commedia dell’arte to the National Theatre’s hit play One Man Two Guvnors. They were comedies, The Irishman isn’t, but it is not beyond the realms of reason that Netflix ends up laughing all the way to the bank with a hit Hollywood rejected.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter