Image copyright

Image copyright

Reuters

“Even as a little child,” Guzmán’s mother said, “he had ambitions”

Caked in filth, the world’s most powerful drug baron hauled himself from a manhole.

For Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, whose feats of escapology were matched only by his drug-smuggling acumen, it was a trademark yet ultimately futile manoeuvre. The 17 Mexican marines raiding his ranch nearby would catch him soon enough.

Six months earlier, he had humiliated Mexican authorities by fleeing Mexico’s most secure prison, his second jailbreak in two decades. This time he would not slip through their fingers, although those who caught him were left in no doubt how angry he was to have been arrested.

“You are all going to die,” he warned police in the hours after his capture in Los Mochis, north-west Mexico, on 8 January 2016.

Three years on, Guzmán has been handed a life sentence, plus 30 years, after being found guilty of international drug smuggling in a lurid three-month trial that exposed his criminal empire.

At his sentencing in New York, Guzmán said he had received an unfair trial and his treatment in solitary confinement was tantamount to torture.

“We’re never going to see his like again,” Douglas Century, the author of the book Hunting El Chapo, told the BBC.

Guzmán was the oldest of seven children born into a poor family in the rural community of La Tuna in Sinaloa state, north-west Mexico.

His parents – Emilio Guzmán Bustillos and María Consuelo Loera Pérez – earned their living from farming. His father was officially a cattle rancher but is believed to have been an opium poppy farmer, Malcolm Beith writes in his book, The Last Narco.

Guzmán’s enterprising spirit was apparent from a young age. He would support his family by selling oranges to peasant farmers for a few pesos. His penchant for the spoils of wealth didn’t go unnoticed, either. In a Vice News podcast, Guzmán’s younger sister Bernarda said he would wear fake gold jewellery when visiting family members.

“Even as a little child, he had ambitions,” his mother told filmmakers in 2014. She recalled he had “a lot of paper money” which he would count and recount.

His first foray into organised crime came at the age of 15, when he cultivated his own marijuana plantation with his cousins. Then, he adopted the nickname “El Chapo” – Mexican slang for “Shorty”. But his ambitions belied his diminutive stature (he is only 5ft 6ins, or 1.64m).

In his late teens, Guzmán left La Tuna to seek his fortune in drug smuggling. “He always fought for a better life,” his mother said.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Guzmán’s mother arrives at the US Embassy in Mexico City in June 2019

That better life would come at a cost, paid for by illegal drugs and years of bloodshed. From his beginnings as a hitman, Guzmán’s rise through the ranks of the criminal underworld was swift.

Former cartel kingpin Héctor “El Güero” Palma gave Guzmán his first break in Guadalajara in the late 1970s, when he oversaw a shipment of drugs from the Sierra Madre mountains. Guzmán was ambitious and eager to increase the quantities of drugs being transported, according to Mr Beith’s book, The Last Narco. He was also “no-nonsense” and would execute employees himself if deliveries were late, Mr Beith said.

Guzmán’s reputation for ruthless efficiency was duly noted. In the 1980s he was introduced to Miguel Ángel Félix Gallardo – known as the Godfather of the Guadalajara cartel – who put him in charge of handling logistics.

When Félix Gallardo was arrested in 1989, his cartel’s drug trafficking territories were divided among different factions, later known as The Federation. Guzmán was a beneficiary, setting up his own Sinaloa cartel with other traffickers in north-west Mexico.

In the 1990s, he honed his operation, pioneering the use of sophisticated underground tunnels to move drugs across the border.

“He was the go-to guy,” David Weinstein, a former federal prosecutor in Miami, told the BBC. “When the United States started shutting down ports of entry in the Atlantic and Pacific in the 1990s, drugs had to go through Mexico. And if it had to go through Mexico, it had to go through El Chapo.”

Media playback is unsupported on your device

He invested his proceeds wisely, not only expanding his enterprise, but building infrastructure that benefited locals in Sinaloa too. This cemented his popularity. “You are Santa Claus. And everybody likes Santa Claus,” Eduardo Medina Mora, Mexico’s former ambassador in Washington, told the New Yorker in 2014.

Over time, Guzmán’s cartel became one of the biggest traffickers of drugs to the US and in 2009, he entered Forbes’ list of the world’s richest men at number 701, with an estimated worth of $1bn (£709m).

As his wealth and empire grew, so too did scrutiny from law enforcement. “The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) have been after him for decades,” Mr Weinstein said.

In 1993, a Roman Catholic cardinal was shot dead in a turf war with rival drug smugglers. Guzmán was among those blamed and a bounty was placed on his head by the Mexican government. His moustachioed face, previously unknown to the public, started appearing in newspapers and on TV screens. Within weeks, he was arrested in Guatemala and he was later sentenced to 20 years in prison on charges of conspiracy, drug trafficking and bribery.

A prison psychological profile described him as “egocentric, narcissistic, shrewd, persistent, tenacious, meticulous, discriminating, and secretive”, according to the New Yorker. In prison, he enjoyed a life of luxury, smuggling in lovers, prostitutes and Viagra, according to reports in Mexico.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Mexican Navy soldiers escort El Chapo Guzmán in February 2014

Eight years behind bars was enough for Guzmán. In January 2001, he broke out of a top-security jail, Puente Grande. He did so, as the myth goes, in a laundry cart. What’s more likely, multiple journalists and authors argue, is that he simply walked out of the door with the help of corrupt guards.

Guzmán controlled the prison to such an extent he escaped in police uniform, Mexican journalist Anabel Hernández wrote in her book, Narcoland. Guzmán would spend the next decade evading authorities and consolidating his power as Mexico’s pre-eminent drug smuggler. In that period, he always seemed to be one step ahead of would-be captors and rival cartels.

“He’s a micro-manager,” said Mr Century, who co-authored his book with Andrew Hogan, the undercover DEA agent who caught Guzmán in 2014. “In the text messages we have, he’s in the weeds of every single minor facet of his drug operation.”

Sex was his other preoccupation, Mr Century said. “He had more mistresses than you can probably fathom. This was his existence: having sex with strange women and micro-managing every detail of his operation.”

After 13 years on the run, Guzmán was captured by Mexican marines called in by Mr Hogan in February 2014. Guzmán’s second prison break, in July 2015, was arguably even more fantastical than the first. This time, his accomplices used GPS to burrow a 1.5km (one mile) tunnel that led directly underneath his cell in Altiplano prison in central Mexico.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

The escape was elaborate and carefully planned. The tunnel had ventilation, lighting and stairs and the exit was hidden by a construction site. Mexican TV stations later aired footage that showed that guards failed to act when loud hammering was heard from inside Guzmán’s cell.

Guzmán had embarrassed Mexico’s government for the second time, leaving then-President Enrique Peña Nieto “deeply troubled” and “outraged”.

His freedom, however, was short-lived. In January 2016, Guzmán was tracked down to a house in an affluent part of Los Mochis in northern Sinaloa. Five of Guzmán’s guards were killed in the raid by Mexican marines and he managed to flee out of a manhole, but was caught in a car while leaving town. One year later, he was extradited to the US.

Image copyright

Getty Images

This motorcycle, adapted to run along a track, was used by Guzmán to move through the tunnel

His Achilles’ heel, Mr Century told the BBC, was his narcissism. He was reaching out to actors and directors to commission screenplays about his life, Mr Century said. His communication with actors and producers gifted Mexico’s attorney general a new line of investigation.

“When he escaped from prison in 2015, he probably could have run away to the mountains and just lived,” Mr Century said. Instead, Guzmán made the unprecedented move of granting an exclusive interview to Hollywood actor Sean Penn in October 2015. It was a decision that may have cost him his freedom.

“I have a fleet of submarines, airplanes, trucks and boats,” he said in the interview published in Rolling Stone magazine. After his capture it was speculated – though never formally confirmed – that Mexican authorities found Guzmán by tracking Penn. “He contacted actresses and producers, which was part of one line of investigation,” said Mexico’s attorney general, Arely Gómez.

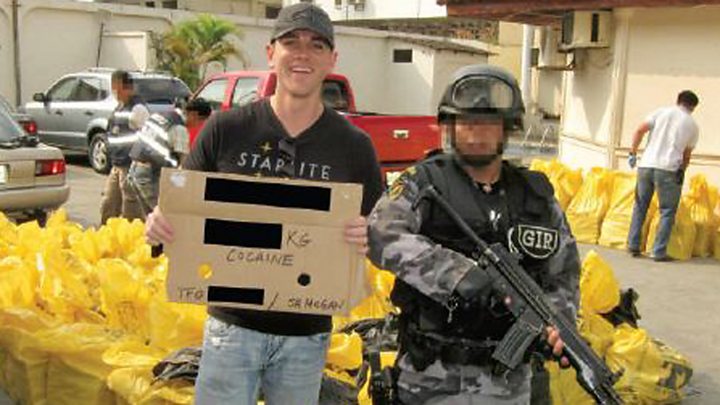

Image copyright

Reuters

Did this meeting with Sean Penn bring about El Chapo’s downfall?

Facing a life sentence at a “supermax” prison in the US, Guzmán’s fleet is of no use to him now.

Over his 30-year criminal career, he is believed to have earned more than $14bn (£11bn) in cash proceeds from narcotics sales, the US Department of Justice said. So far, the value of Guzmán’s assets has proven difficult to verify. Forbes even removed him from its billionaire rankings over verification concerns.

The $14bn figure is too high, Bruce Bagley, a Mexican drug cartel expert, argued. He told Forbes that most Mexican drug lords plough their revenues into “operations and protection”, estimating that “El Chapo probably makes well below a billion per year”. Mr Weinstein said the $14bn figure was not unrealistic, but doubted the full amount would be recovered.

Image copyright

Getty Images

El Chapo Guzmán arrived in New York under heavy escort in 2017

Some of his assets were mentioned during his 11-week trial in New York. A former cartel member told the court Guzmán bought homes in every state in Mexico. Miguel Angel Martinez said Guzmán was so wealthy, he had a private zoo, a $10m beach house and yacht he named after himself (“Chapito”), the court heard.

The most jaw-dropping revelations, however, were not about his wealth.

BBC reporter Tara McKelvey covered the trial, which started in November 2018. She said the courtroom “looked like a real-life movie”, the jurors watching intently as they would a Netflix show.

Image copyright

Getty Images

The wife of El Chapo Guzmán, Emma Coronel Aispuro, arrives at court in New York in January 2019

His beauty queen wife, Emma Coronel Aispuro, she said, “looked bored most of the time” – even when Guzmán’s former mistress testified. While Coronel remained placid, the trial’s astonishing moments shocked others.

One witness, for example, told the court Guzmán buried a man alive. Another told of a rival narco chief who refused to shake Guzmán’s hand – and paid for it with his life. Court papers also accused him of drugging and raping girls as young as 13, calling them his “vitamins”.

The scale of his drug trafficking operation was laid bare, too.

Image copyright

Reuters

El Chapo Guzmán and his defence attorneys are seen in court in New York in January 2017

Assistant US Attorney Adam Fels alleged that Guzmán had sent the equivalent of more than a line of cocaine for every single person in the US in just four shipments. And to protect his businesses, a bribe of $100m (£77m) was paid to former President Peña Nieto when he took office in 2012, it was alleged in court. Mr Peña Nieto strenuously denies the allegation.

When Guzmán’s guilty verdict was read aloud, his mouth was “agape” and he looked “vaguely stunned”, the New York Times reported.

In a trial that attracted podcasters, screenwriters and true-crime obsessives, some observers said the media attention trivialised the proceedings. The intention was quite the contrary, our correspondent said. The trial was meant to be a public spectacle to show what El Chapo and his henchmen had done and to send a warning to others, she said.

The title of Mr Beith’s book, The Last Narco, suggests Guzmán is one of a dying breed of ultra-violent drug barons as bloodthirsty as they are shrewd.

Yet, while Guzmán is likely to die behind bars, Mexico’s drug-smuggling problem is likely to outlive him. In his Rolling Stone interview, Guzmán said it was false to assume drug trafficking would cease “the day I don’t exist”.

For all his supposed vanity and self-confidence, not even Guzmán can claim to be the last narco.